Monday

Jul302007

What's your feed reading speed?

Monday, July 30, 2007 at 1:46AM

Monday, July 30, 2007 at 1:46AM If you can't measure it, you can't manage it. -- Peter Drucker? [1], [2]As a follow-up to Afraid to click? How to efficiently process your RSS feeds I decided to time a few of my RSS processing and organizing [3] sessions. I've included the results below, with average time spent/post in bold. (Note: See the above article for the simplified workflow I use.)

Here are the results:

Test 1

# : 139 posts

avg : 33 minutes / 139 posts -> 14 seconds/post

Test 2

# : 81 posts

avg : 26 minutes / 81 posts -> 19 seconds/post

Test 3

# : 242 posts

avg : 43 minutes / 242 posts -> 11 seconds/post

Test 4

Crucial to rapid processing is having a great follow-up system - especially an Actions list (I have a "To-Print" sub-category) and a Read/Review cache.

# : 132 posts

avg : 22 minutes / 132 posts -> 10 seconds/post

hits : 24

7 new to-read articles, 4 posts to reply to

On curious thing I noticed: When I'm timing myself I'm much more aware of the two minute rule, which results in a more focused, more efficient session.

So how does this compare with your speed? I'd be very curious to hear some of your stats!

Note: If you try this experiment for yourself, you might also want to track how many "hits" you had, i.e., how many of the total # of posts passed the first phase. In Firefox you can get a quick count of open tabs by closing the window. It will ask you to confirm, and the message contains the count: "You are about to close ____ tabs. Are you sure you want to continue?". WARNING: It's possible to turn this off, so first do a dry-run, or bookmark the group of tabs (control-shift-D in Firefox) just in case!

References

- [1] This quote is often attributed to Peter Drucker, but a bit of digging indicates it's not that clear. Searching for the phrase - and the original "If you can measure it, you can mange it" - yields some surprises. For example, A Hacker's Guide to Project Management credits it to Tom DeMarco, who starts with it in his book Controlling Software Projects: Management, Measurement, and Estimates.

However, going back a bit, the book Measuring the Value of Information Technology says it was Lord Kelvin who originated it:It was the scientist Lord Kelvin who said, "When you can measure what you are speaking about, and express it in numbers, you know something about it; but when you cannot measure it, when you cannot express it in numbers, your knowledge is of a meager and unsatisfactory kind; it may be the beginning of knowledge, but you have scarcely in your thoughts advanced to the stage of science." Later, this statement was abbreviated to "if you can measure it, you can manage it," and "if you cannot measure it, you cannot manage it."

BUT, even further back the authors of Geography Matters! state "The Renaissance astronomer Rhaticus suggested that if you can measure something, then you have some control over it." Wikipedia has more at Rheticus. - [2] You might also enjoy To Improve Productivity, Measure It First.

- [3] More at How to process stuff - A comparison of TRAF, the "Four Ds", and GTD's workflow diagram.

- [4] For bloggers this is why you should use great titles (see 8 Ways of Creating Compelling Blog Post Titles). Sadly, I admit I should use more care in titles. For example, instead of Four small Gmail tweaks Google could make to increase user productivity, it should have been more dramatic, e.g., "Four small Gmail changes that could save the world $500M" :-) Oh well, something for my lessons learned file!

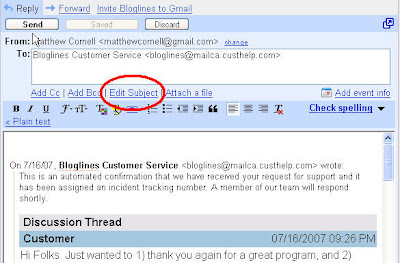

- [5] Exceptions: Email-based feeds, which have no corresponding URL to view - must be read in situ. See Move email-based subscriptions to RSS for why you should not be receiving news via email.